Episode 2 - VPNs, Reverse Proxies, and Ockam

Matthew Gregory CEO

Published 2024-01-20

Transcript

Matthew Gregory: Welcome again to the Ockam podcast. Every week Mrinal, Glenn, and I get together to discuss technology, building products, security by design, and a lot more. We'll comment on industry macros from across the cloud, open source, and security.

On the first podcast, we went through why we're here, what Ockam is, and a little bit about the background so everyone can get to know us. On today's episode, we want to dive into some technology and get into the good stuff. So we thought we'd go through a couple of common ways that people connect applications and distributed systems. You have to presume that we live in a world where applications and data are distributed across clouds. And when I say clouds, I use that in the broadest way possible. Snowflake is a cloud, a windmill or a Tesla is a cloud, it's whatever that environment is. It's running applications.

We were talking to the solutions engineer at the Google Cloud conference, and we were describing distributed applications, and his pushback was: why don't we just run everything in the same VPC, problem solved.

Good luck with that. We're a pretty small company, our infrastructure is pretty simple. We have things connected all over the place, right? It's a funny retort, that people could pull that off. Running everything inside one box.

Cloud architectures have become exponentially more distributed.

Glenn Gillen: It just doesn't happen in the real world these days. Does it?

Matthew Gregory: Exactly. You're going to want to run data lakes like Snowflake and have them manage your data. You're going to want to do analytics with Datadog.

Enterprises have multi-cloud and on-prem systems. People are still moving to the cloud. They're just not lifting and shifting the whole infrastructure.

Mrinal Wadhwa: I think people experience the internet from their own perspectives, social media is not the same for everybody. Similar people view the cloud through whatever infrastructure or application they are managing and how widely it distributes. Most company's applications and systems tend to be across clouds. Oftentimes you're communicating across companies, you're communicating to systems that might live in a different geography all the time. So things are distributed and becoming more so.

Glenn Gillen: I got sucked into that a little bit myself. Working at AWS, even when customers told you they were all in AWS, the reality is that there's a lot of their workload running in AWS but there are still people in an office somewhere that need to connect to those things. Or remotely from cafes and home these days. So there are still multiple environments that need to be connected in some way. Being in a single cloud is not an observed reality, except in anything but the smallest mom-and-pop shop setups.

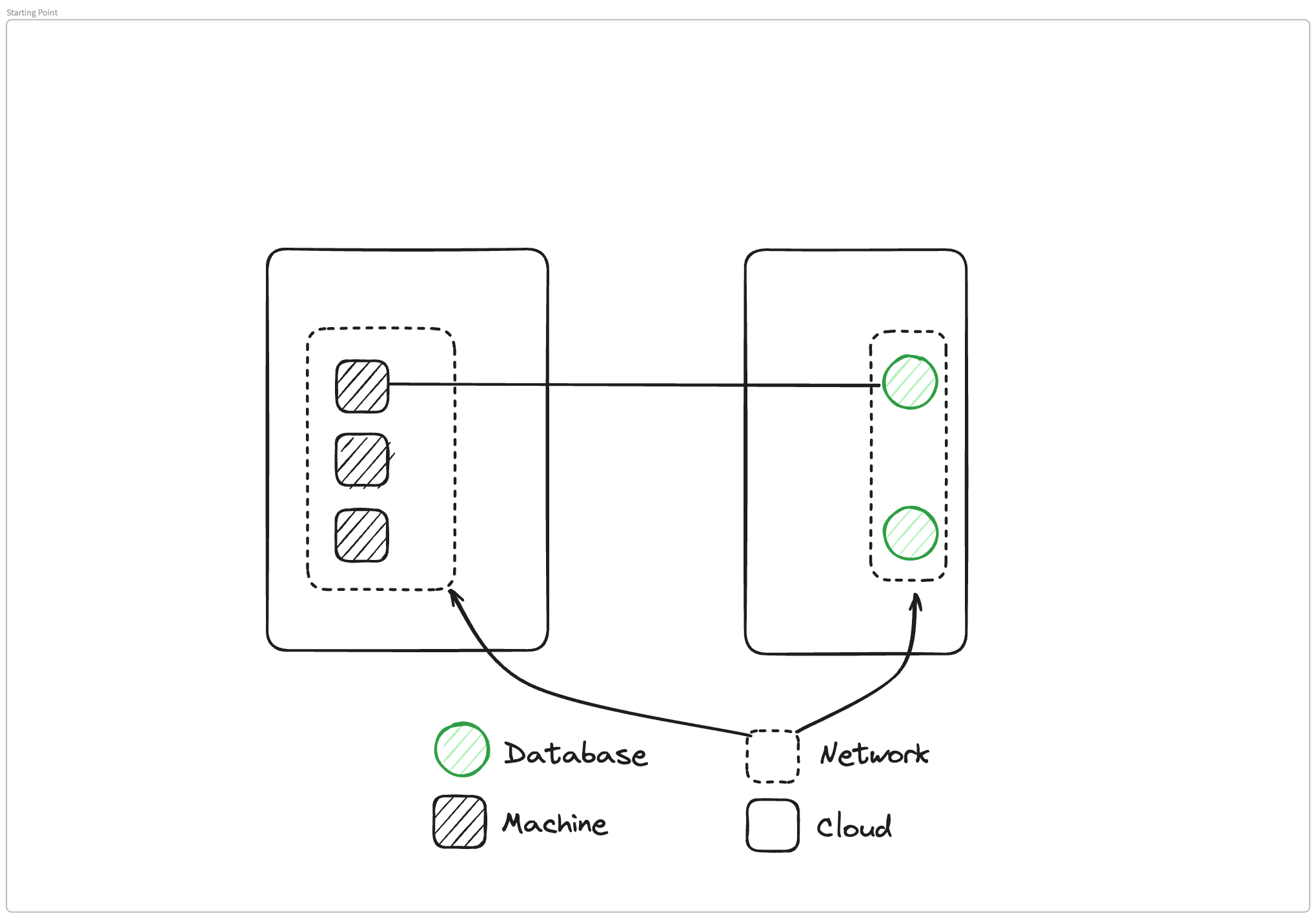

Let's establish the base case architecture

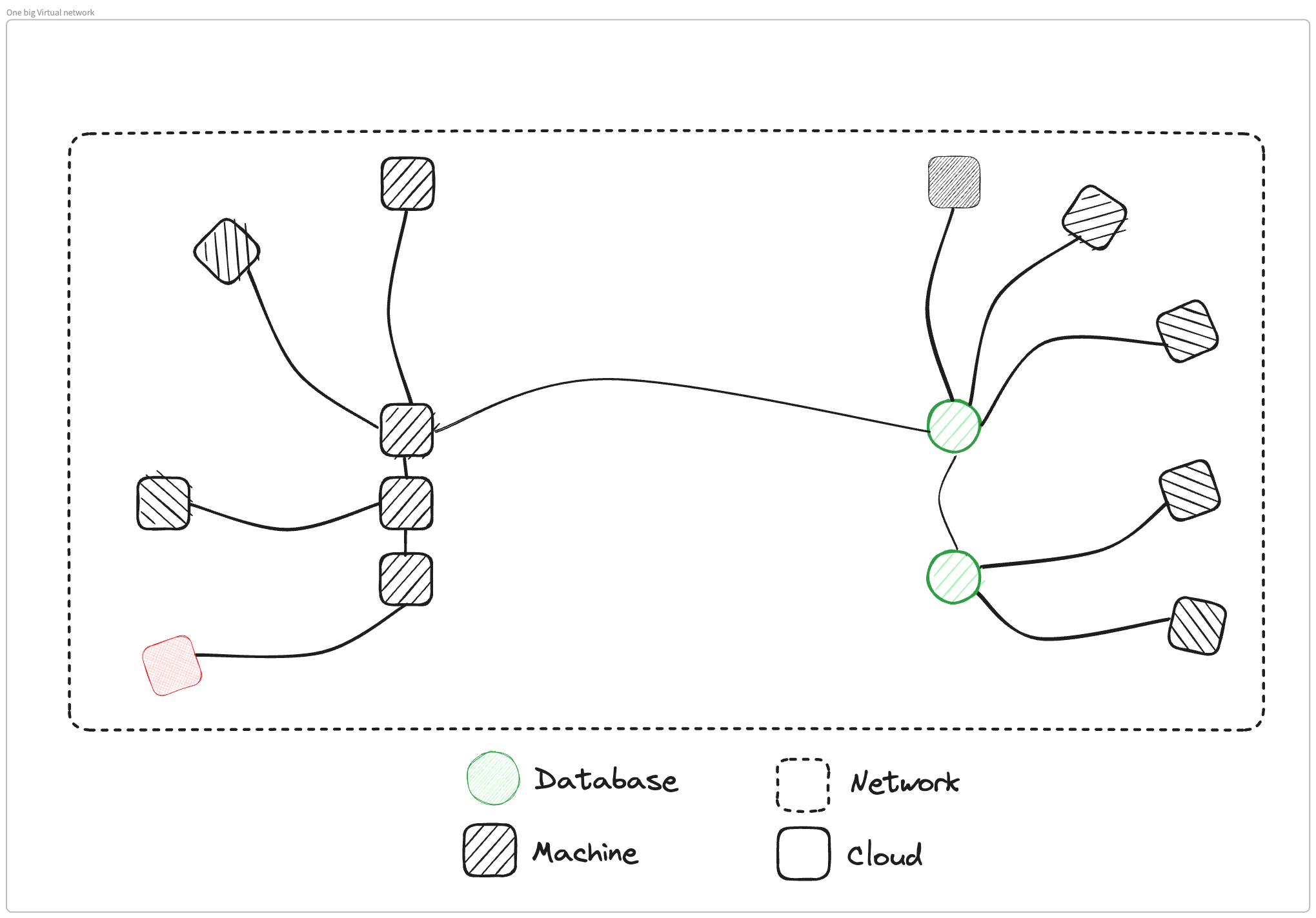

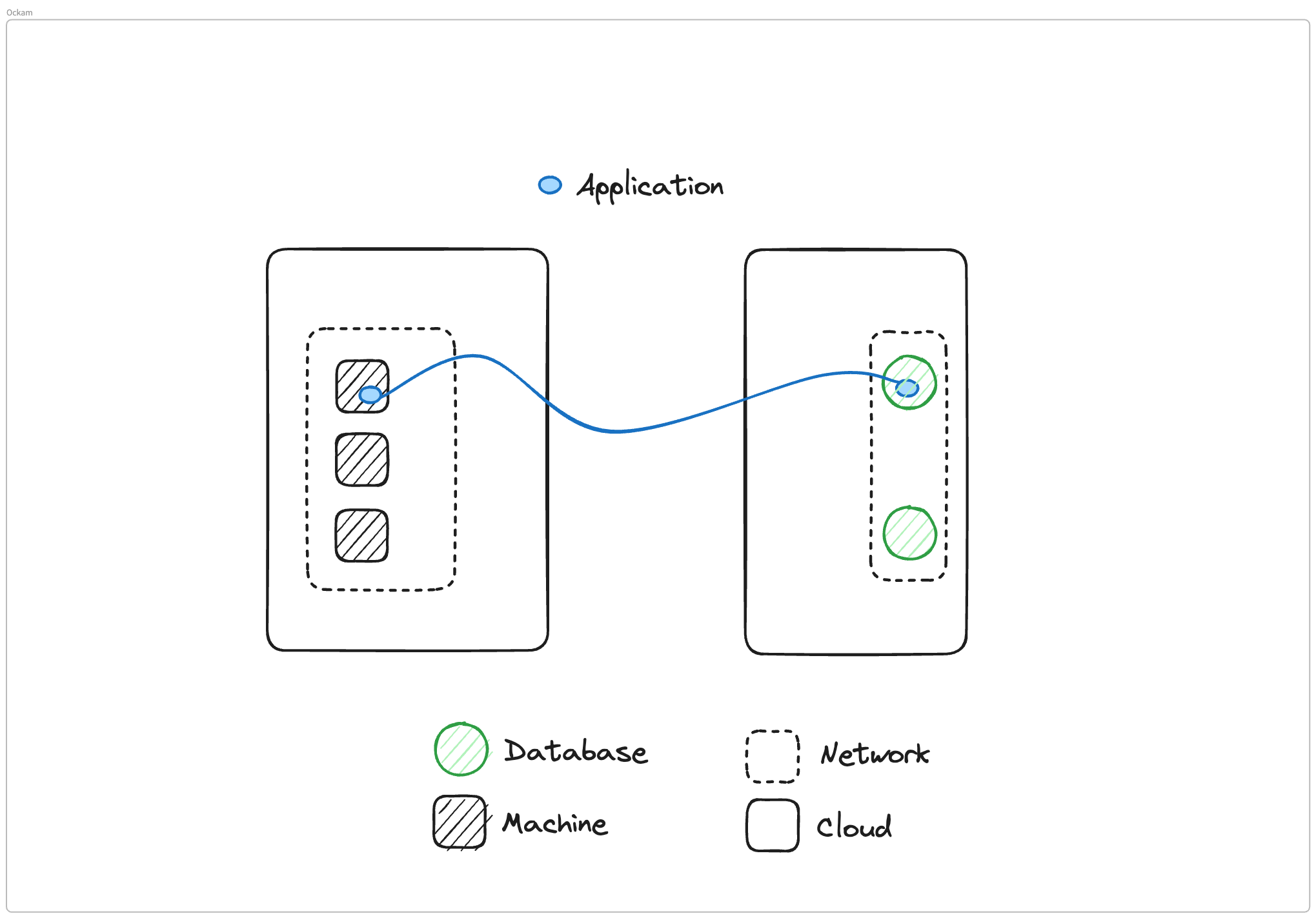

Matthew Gregory: Okay, so let's switch over to this base case here.

What I've set up is a very simple architecture, we have two different clouds or two different pieces of infrastructure. In one of them, we have a VPC or a network boundary, and inside that we have three different machines. In the other cloud, we also have a network boundary, another VPC, and two databases.

What we need to do is we need to connect one of these machines to one of these databases so that the applications inside the machine can connect to the database. We'll go through three different ways you could make this connectivity happen.

VPNs are the 'classic' way to connect remote machines.

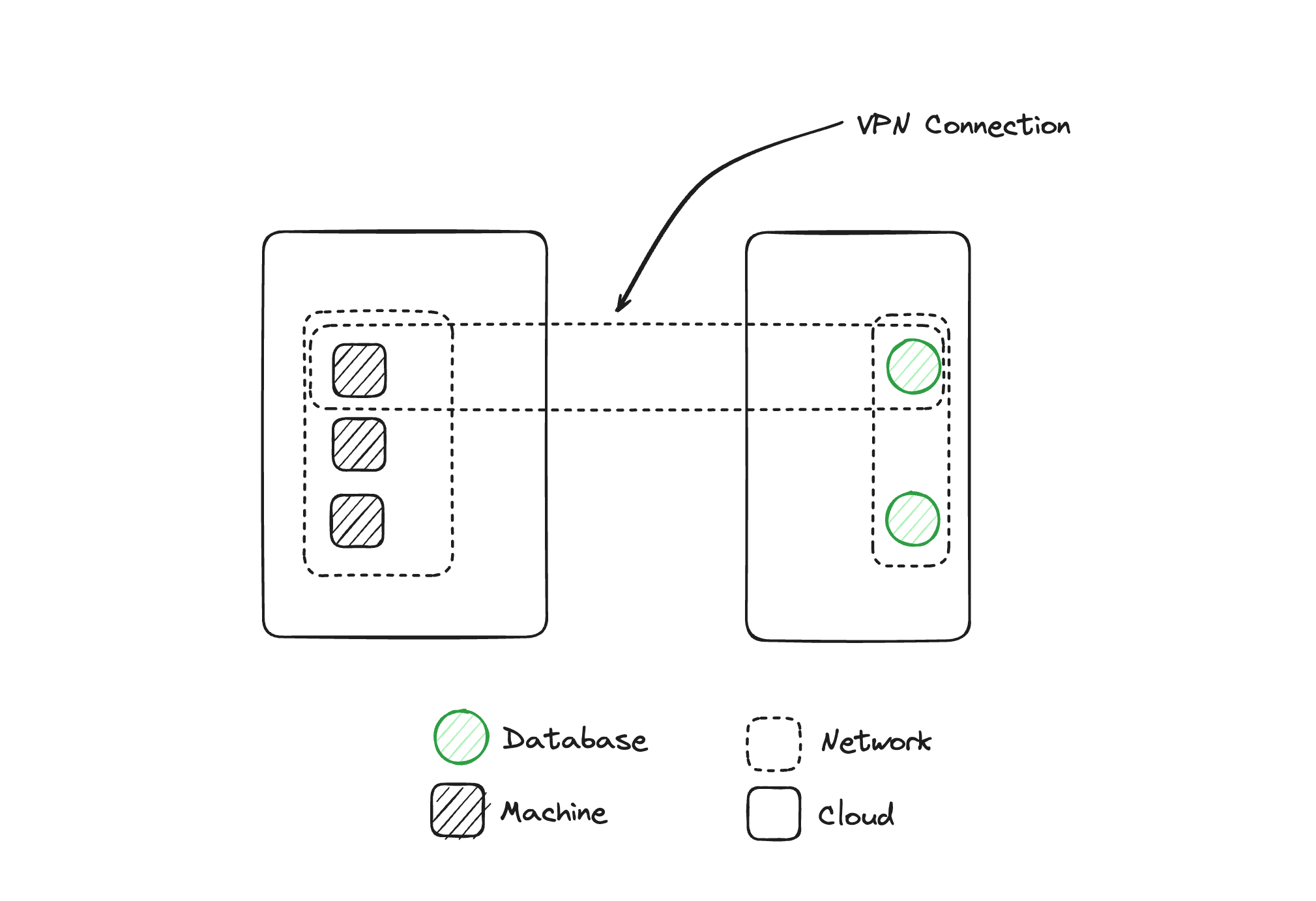

First, we'll talk about how we could set this up with A VPN. We'll also talk about how we could set this up with a reverse proxy, and then we will talk about how we could set this up with Ockam. And what you get is the difference between each of them. We'll start with the VPN.

In this one, what we are doing is we're setting up a new network that encapsulates. One of the machines is on the left and the database is on the right. And with this virtual network boundary, we can now move data from our database to the machine and back and forth because they're now inside the same boundary. Glenn, you have a really good mental model for what's happening here, and could you talk a bit about how you think about virtualizations in the cloud world?

Glenn Gillen: If you scale this problem down to something that was physically in the same spot, one of the solutions you would do here is put a network card into both machines and you'd attach them via cable, or connect two routers, assuming they're in different networks, you'd find a way to physically plug those things into each other.

And that's ultimately what a VPN is doing, but at the software layer. You install a virtual network interface, and then you're running essentially a virtual cable between those two points. I've always found that to be a useful way to think about this. You are connecting things so that they can then get access to each other, whether it be two networks, two routers, two machines, whatever it is.

There are a bunch of similar properties between connecting things in the physical world and connecting those two networks.

Mrinal Wadhwa: I think that's a really good way to think about it. If you look at it from the perspective of each machine involved in a VPN, that machine effectively becomes connected to a virtual network interface card, right? As you were describing, Glenn.

Now what happens is that the machine has a virtual IP on this network interface card. And it has a physical IP on some other network. Now effectively, what you have is two IP ranges or two networks connected to a single machine.

So effectively this machine becomes a little router. As long as someone can figure out a way to traverse these routes, they can jump networks using a VPN. What you've got looks a lot like physically connecting the machine that's running that database to a machine in another network. These two are now virtually connected at the machine level.

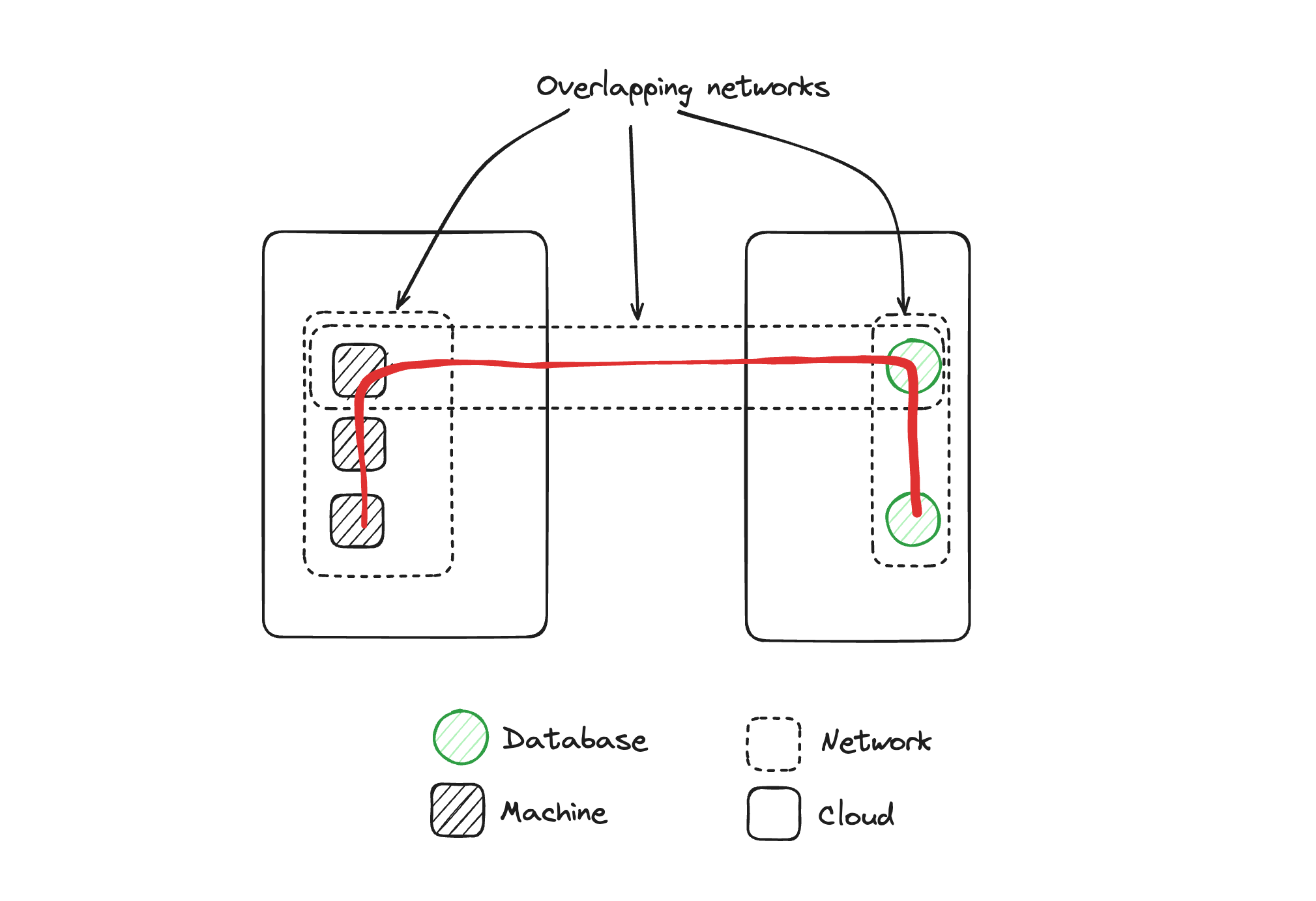

Matthew Gregory: That brings up a question. If we go back to the first diagram, we had two networks that were physically disconnected from each other, so there was no way for something in the left environment to engage with the right environment. We need to move data between these networks, so we need to connect them in some way. So we created this third virtual network. Now we have two machines that are not part of this VPN and a database that's not part of this VPN but are part of the same network that the machine and the database that are inside the VPN are connected to. Mrinal, what can happen in those scenarios?

Risks with VPNs: Lateral movement and cloud scale lead to tooling bloat.

Mrinal Wadhwa: The key thing is that there are now three networks and all three of them have connectivity between them, right? Because those two machines are in two networks each, what we've got now are these three overlapping networks that are connected to each other.

What that effectively means is even though we intended to connect one machine to one database, what we've got is the ability for machines in one of the networks to potentially reach the database in the other network. Because there are now connections between these three networks, we must think about all the controls to make sure this cannot happen, and make sure there are no bugs in the programs that are making these connections. Effectively what we've got is three overlapping networks acting like one network.

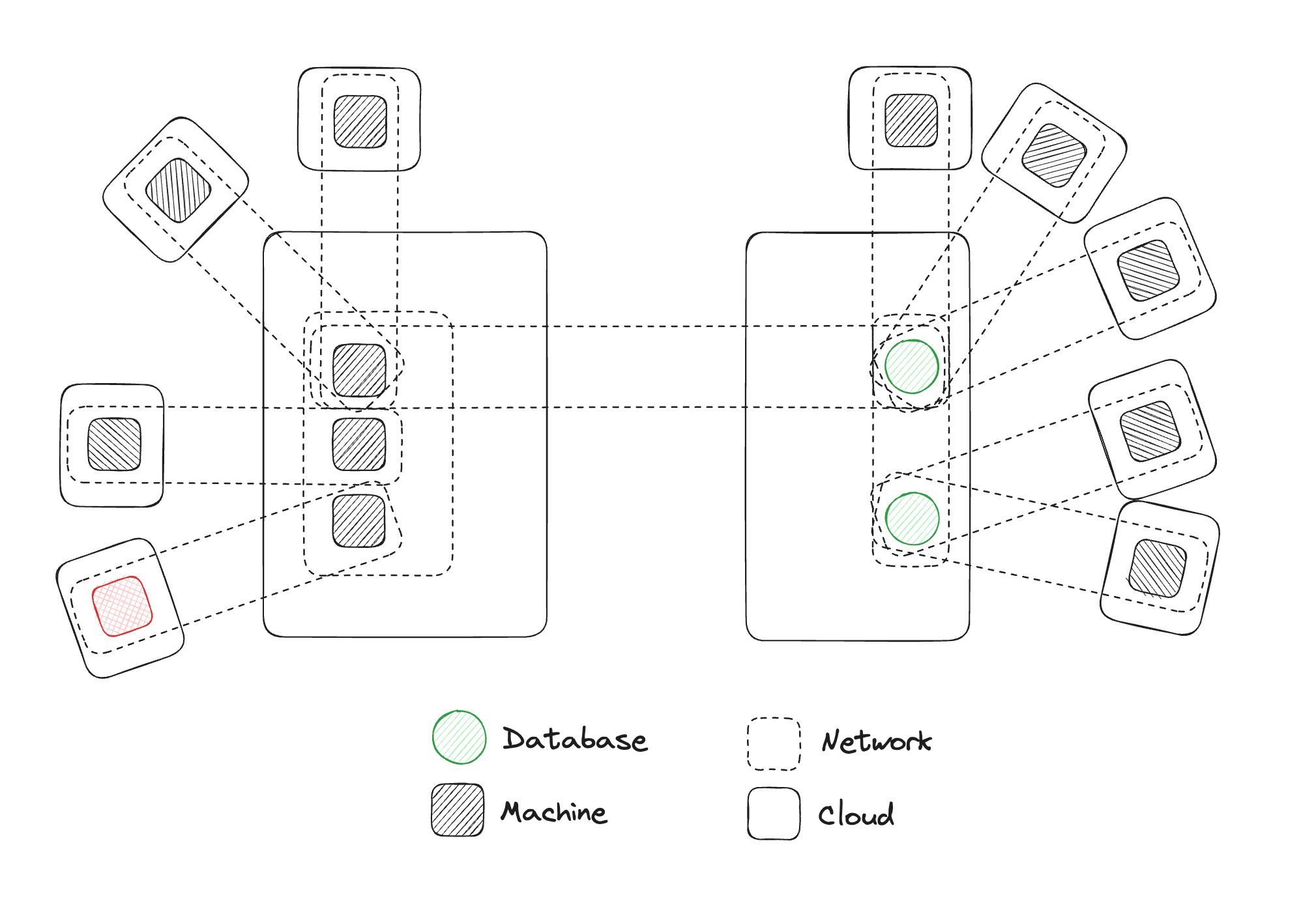

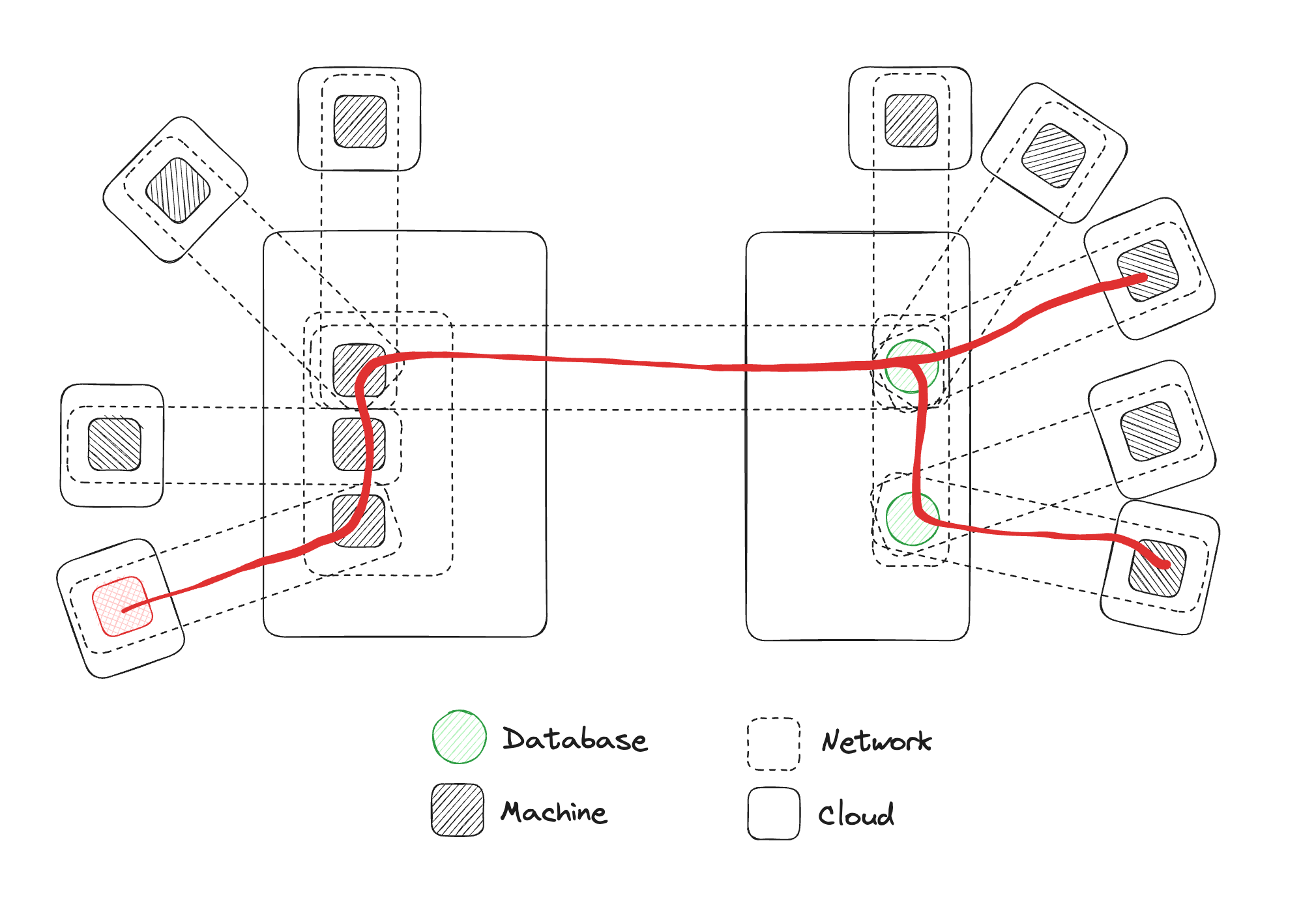

Matthew Gregory: For the point of illustration, I created a more complicated version. This diagram is trying to articulate the reality that we live in where there are multiple clouds, with multiple networks, with multiple machines. I've added a bunch of other clouds, networks, and machines to this topology. This is very indicative of a particular customer that we're working with. They deploy machines into scientific environments, and they want those machines to be able to write data to their data cloud.

One of the problems that they have is, as they describe it, the networks look like Swiss cheese. They have this very simple topology where they're trying to add a machine to a network and have it write to another network, but they have no control over the network. They don't know what other VPNs exist in the network. So they're just trying to do this one-to-one connection, but they're deploying a machine into an environment where anything could be happening there.

Glenn Gillen: There's a bit of a disconnect when you start talking about VPNs because people mentally segment the network and this virtual thing over the top of the network. But essentially it's just more of the network. You end up back at the same place as though you were plugging all those things in. And if you're plugging those things in, you'd be much more aware of the Swiss cheese you've created for yourself by giving all these different things access to your network.

Matthew Gregory: That's right. That's a great segway into the next diagram, which is what you get when you start connecting things with VPNs.

You'll notice that there is no concept of infrastructure or clouds in this. Essentially what we have is one big network with a bunch of machines and databases, they're all connected with a cable, to use that virtual metaphor of connections.

What we are getting is this one big network with all the machines connected to each other via other machines.

Mrinal Wadhwa: And because all these things are now connected and you have this problem of potential lateral movement, what's useful to think about is, how is this all working?

The way it's working is there is a VPN server somewhere on the internet, and every participant in a VPN makes an outgoing connection to that server. They may do various approaches to NAT traversal in that setting, but they make this connection to this central server. And over that, there's usually some sort of security protocol like IPSec or WireGuard that then sets up these secure channels over this network layer path. So you've got IPSec or WireGuard, which sets up a secure connection between the participants and the machine. And then over this secure connection is a virtual IP network.

Because you have this virtual IP network, any attacker tooling or any scan tooling that can operate on the IP level, where it can scan all the IPs available in a particular network is now tooling an attacker might be able to leverage to map out this network. They can find lateral movement points, and attack things that you weren't intending to connect because they're available at the IP layer. Even though you intended to create one connection, other machines or databases might be reachable over the IP network.

So an attacker who compromises one machine can run scans and attacks to try and compromise another part of the network even though your focus was just this connection. Keep that picture in mind. There's a way of routing packets around, on top of that, there is a secure channel, and on top of that, there's a full virtual IP network that's created with a VPN.

Secure by design: Do we want the 'doors open' or 'doors closed' by default?

Matthew Gregory: In fact, you'll notice I added this little red machine over here. This is a machine, for this illustration, that has malicious code running on it that wants to do bad things in the network. This is a good opportunity to bring up one of the topics we talk about when thinking about secure by design, the concept of starting with all the doors open or all the doors shut. And what we have here with this VPN diagram is a world where all the doors are open. If we think we might end up with malicious code in one machine, we have to do something on the other machines to try to prevent traversal of our virtual network, and an attacker doing something malicious in this other machine where our customer data might be living.

Glenn Gillen: I first got introduced to concepts similar to this when I was building highly reliable distributed systems and the human processes around that as well. Either you are designing systems and processes where everything needs to go right, or are designing them in a way where multiple things have to go wrong.

That's secure by design philosophy. Are you dependent on everyone getting everything right all of the time for your system to be secure? Or does it require multiple points of failure for things to break? If you start from a place where everything has to go wrong and then you're hosed, you are naturally by design in a much more secure place. I didn't appreciate this until I joined Ockam, but a common VPN use case in places I've worked is as follows: I want to do some ad hoc reporting on something. We have a data warehouse, a Postgres service, or something that I need to access that we don't want on the internet.

Often a VPN connection is how you connect to that thing. We just took that for granted, that's just the way you did things, they're the tools you're familiar with. And it wasn't until, you know, speaking to you both ultimately that I thought it was a little bit nuts.

If you take that scenario where I want to access this database, and what we do is run this big virtual cable from your machine into the network where this database runs. That's not how you do it in the real world, no one would realistically run a cable into that database.

But that's what we do, we do it virtually because it's quick and easy. We're familiar with it. But then you get into this place where now we need to lock down the firewall rules and the access control. We've opened up this big pipe and now we need to do a dozen things to make sure we've closed it back down, just to solve for that one particular connection. I just wanted to access a Postgres process that was running on one machine, but you've opened up the world to me and now you're having to do all this work to close it back down.

Matthew Gregory: Another way to put it is, we want a machine to be able to access some data. So we're going to create a virtual network between the two, so we can pass things back and forth. But we keep doing this again and again. And add more and more complexity to the point that we've connected everything, but now we need 15 other security products to start locking things down. This is the metaphor "start closing all the doors." Just walk around the RSA conference. There are 50 things you can go by to fix the VPN nightmare that you've created for yourself.

The question that this begs is, is there just a better base assumption? We think there is, and we'll get, we'll get to that, we are saving it for the end. But let's move on to another common topology here, let's talk about reverse proxies. These are very common, they've been around forever. All the cloud providers have them, CloudFlare has a reverse proxy, and ngrok has a reverse proxy. It's a very common way to connect things, maybe equally as common as VPNs.

Glenn, why don't you run through what's happening in a reverse proxy?

Reverse proxies are a way to make a private app/DB ... public.

Glenn Gillen: For the common database access use case I just mentioned, a VPN solution works fine when you've got people who need access. But if that's a valuable asset for a company that you need to share across teams, across different departments, quite often you won't want to give direct access to that thing.

One thing you might do is put a private API in front of the database to give the business or other developers and the organization access to this data in a consistent manner. Now you're running something else that's closer, a reverse proxy, be it a private API or a load balancer. That lets that database effectively get exposed to the internet, you now have an interface that's publicly accessible to some part of the internet.

There are rules that you can put in place to try to scope it back down again. We're back into that VPN story; we've put something private onto the internet and we're using a dozen different things to try and scope it back down and restrict access because we don't want to put the actual database on the public internet.

Decades of best practices taught us that that's probably not a good posture to take. There are many reasons why you want to do that. You're introducing this choke point, essentially.

Mrinal Wadhwa: That's right. Because we don't want to expose the database server directly on the internet, we add this middle layer, which is a good way to do things like load balancing and achieve high availability because you can switch the connection when you bring up a new version of the database or a redundant copy of the database and so forth.

From a security standpoint, it is effectively still exposing the database to the internet. It can be attacked in all sorts of ways because you've now opened this big wide dangerous door. And then what people do is put in all sorts of controls. You might put in some authentication tokens, you might do TLS in the process, but now you're trying to close those doors down. And that comes with a set of challenges that you must now tackle.

Matthew Gregory: This might be the most open door. If we go back to our first diagram, we have a machine that needs to access some data. Let's presume it's the only machine on planet Earth that needs to access this data. The most open thing that you could do would be to expose your entire database to the wide world of the internet. And then you have to start adding restrictions again.

The RSA conference and the vendors there will sell you 50 different solutions for how to undo this and start closing the doors. Every other day we see customer data that's being leaked out of cloud vendors and it highlights that you don't want to expose your database to the public internet and just hope that you've put enough guardrails in place.

Glenn Gillen: One of the other things I would run into when I was a developer was, quite often you're working on a feature branch or something that I want to share with a colleague, a remote company, or someone who's in a different office, or not on the same network as me.

If I'm at home trying to share something, I've got a static IP at the moment. How do you tell them how to access it? Do you set up a port forward on your router? It's a real pain.

And so quite often what you'd reach for is a managed reverse proxy service where you run it, connect it to the development process that's on my machine, that's serving the web pages that I'm editing. And you'd let someone into your local box that way.

But, as you pointed out there, I've put that thing on the public internet. That's the whole point of what I tried to do there is, I've shared this on the public internet. How am I restricting any other random person from accessing that? Well, now I have to put other controls in place to make sure that I'm scoping the world down to just the individual that I want to access it.

Mrinal Wadhwa: And you might have a valid case for putting things on the internet, right? If you're hosting a website that should be accessible to the world and is production-ready. Then, you want a door exposed to the internet. That's by design.

But if you have a database as a service oftentimes they'll give you an address to the database on the internet, and that's not desirable. There are maybe 5-10 clients in your application that need to get to the database. There's no reason for that database to be a public endpoint on the internet. However, oftentimes it is.

So, there's a place for reverse proxies, it's usually in a scenario where you intentionally want to expose an endpoint to the internet because lots of people need to reach that endpoint. In that case, it makes sense to have a load balancer or a reverse proxy exposed.

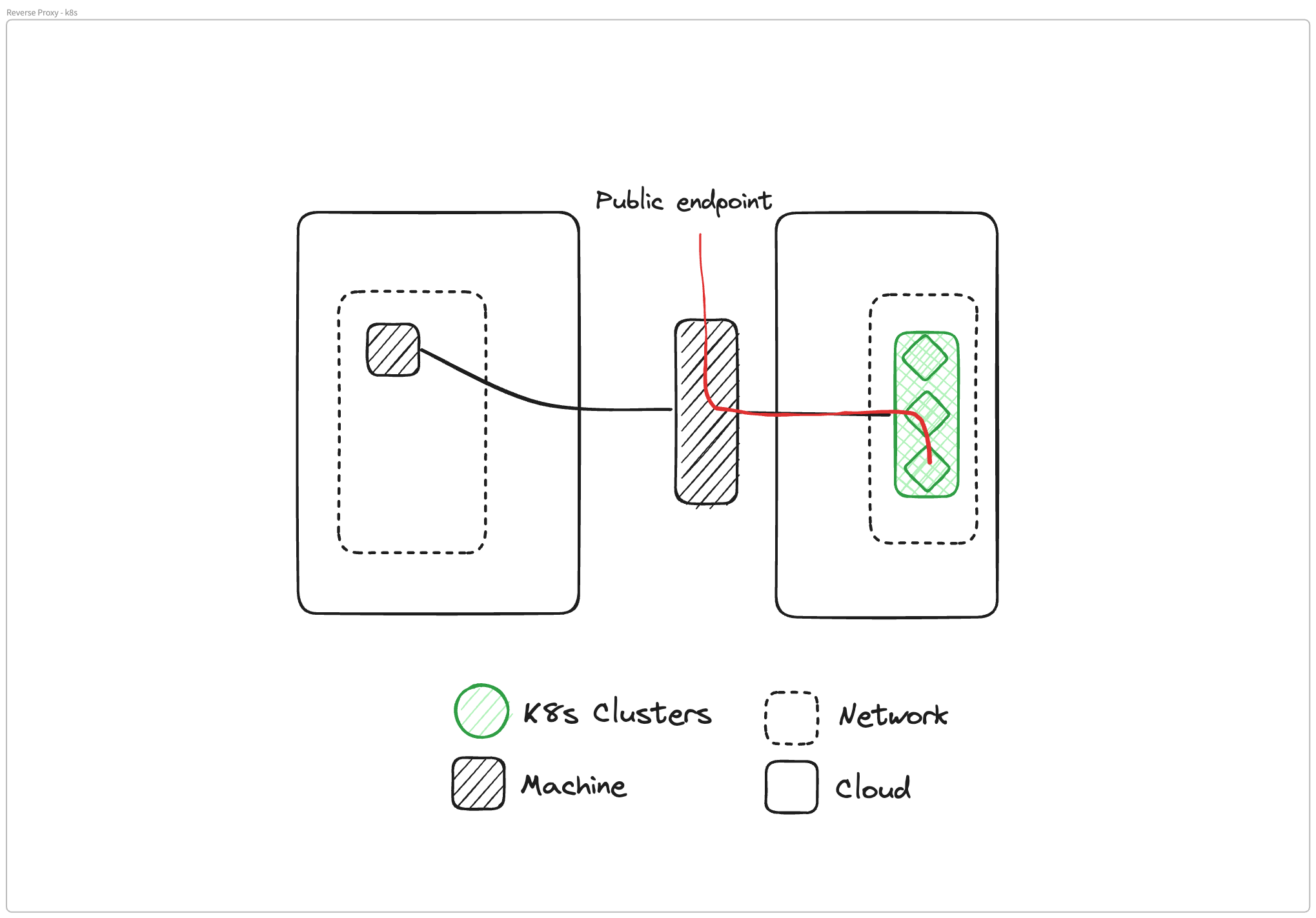

Matthew Gregory: That's exactly right. Let's move on to the next variation of this, which is what we're seeing in the Kubernetes ecosystem. Glenn, why don't you take this one?

Is a managed Reverse Proxy the right ingress controller for a private Kubernetes service?

Glenn Gillen: Let's say you're running pods or clusters of Kubernetes. You have a bunch of microservices that are running somewhere that are serving your business. There's usually a control plane or private APIs there that you need to share across clouds, regions, teams, across other services. And you run into the same problem. You're now in a space where you have to solve for connectivity. How do I get access to the operator? How do I get access to the administrative functions? How do I just make those microservices available?

You very quickly get pushed into a place where you put a reverse proxy in front of your cluster. Now, depending on how it's set up, you have what should have been private clusters available with a public IP address, and all of the problems that come with that. And now you're back to figuring out what our controls are.

What are we putting in place to make sure that we're scoping back access again? This isn't meant to be public, but it kind of is.

Mrinal Wadhwa: Another thing that happens in this case is that you want security end-to-end on these data flows, right? Let's say I have a client application running in Azure and I want to access a microservice in my Kubernetes cluster in Google Cloud. If you use a reverse proxy to make this connection happen, oftentimes your TLS connection is terminated at the reverse proxy.

If you are running the reverse proxy, maybe that's okay, but if a third party is running the reverse proxy, now your application is exposed to the risk of that service provider and how they might be attacked.

Sometimes people put in the work to establish a second TLS connection back from the reverse proxy, which then is mutually authenticated and encrypted all the way back to your Kubernetes cluster. But usually, because that part is complex, people will leave out that part. So you have one TLS connection that is internet-facing, but as soon as the traffic enters behind the reverse proxy, nothing is protecting it.

Even when you have something protecting it, you still have TLS terminating inside the reverse proxy. And now your traffic is vulnerable at that middle point where it's being handed over from one TCP connection to the other one. There are no protections around it.

The right way to do it would be to come up with a mechanism that would allow this connectivity to happen in a way that limits access only to the intended client applications. And it does it in a way that doesn't expose my microservices to all sorts of attacks that may come from the internet.

Glenn Gillen: One assumption people make with managed services is implicitly trusting vendors with all of their data.

It's not about the trust you have in that vendor. Are you building a system where everything has to go right for you to be secure? Or are you building a system where multiple things have to go wrong? Maybe the hyperscalers are at the scale where you've delegated so much trust that it's fine. But you're not trying to protect yourself from a wayward employee who's decided to be nefarious and go and look at your data. You're trying to protect yourself from well-intentioned companies that thought they had a really good security posture, but all it took was one breach and their entire customer base has been exposed.

And that's the risk there is. It's not that you don't trust them to do TLS properly, or you don't trust their employees. If they get breached and someone gets access to that reverse proxy, your data is plain text. It's transferring through that and that's not in your control anymore.

The way TLS works is that the encryption is only good for the length of the TCP connection and that handoff point is a vulnerability spot for you.

Data integrity is as important as data privacy. Let's get serious about integrity.

Mrinal Wadhwa: Oftentimes people miss the fact that when the data is plain text, not only is it vulnerable to theft, it's vulnerable to manipulation. There was some news about Russian attackers sitting inside the Ukraine telecom infrastructure a few days ago. And they were sitting there for years.

Theft of data is scary, but if an attacker is sitting inside someone's infrastructure, they can also manipulate the data as it's flowing, and that can oftentimes have more catastrophic effects than theft. It's worth thinking about how data integrity is guaranteed end to end.

Glenn Gillen: I'm fascinated about this at the moment because I think as an industry we've been so focused on privacy and exposure because it's embarrassing and there's been so much of it over the past couple of years. But especially with this move to AI training models, I think with integrity we're a little bit asleep at the wheel. People are so focused on making sure they don't get exposed.

They haven't put deep thought into the considerations around what would happen if people were just sitting there for two years manipulating the data. Would you have even noticed? What's the long-term strategic impact on the business when you realize that the data lake that you've invested all that money in is just polluted with noise and you didn't realize it? You have no way to fix that.

Matthew Gregory: I have a very specific example here. I was talking to someone, a vendor that has big wind farms and they made the point that their data isn't that special and it doesn't need to be protected because it's just wind speed information that's coming from the wind farm to the data center. And this is effectively public information. There is no real privacy concern. If you just wander out in the field and put up a handheld anemometer, you could look at say it's blowing 18 knots out here. Why would we need to protect that data?

Well, my response was, if I have access to the data as it's moving from the wind farm to the data center, and I change the wind speed from 18 and invert the numbers and make it 81, what does your data center do with that information? Well, it shuts down the wind farm because it thinks that it's exceeded the velocity for safe operating conditions. So it stops the wind farm. So here's a good example of how manipulating data can cause massive destruction from a business point of view, even though this data is essentially public. Wind speed is not something that needs to be kept private, but it's something that you need to rely on to make smart business decisions. In this case, whether or not the wind farm should be operating.

Mrinal Wadhwa: That example is really interesting, Matt. Because you said the data center shuts down the wind farm. My next question is, how does that instruction to shut down operate? I bet it's going over the same channel, which means if I can manipulate data on the channel, I can give the wind farm the instruction to shut down, right?

So that's why you need data integrity. People don't think through this type of impact enough, I feel.

The virtual architecture mental model with a Reverse Proxy.

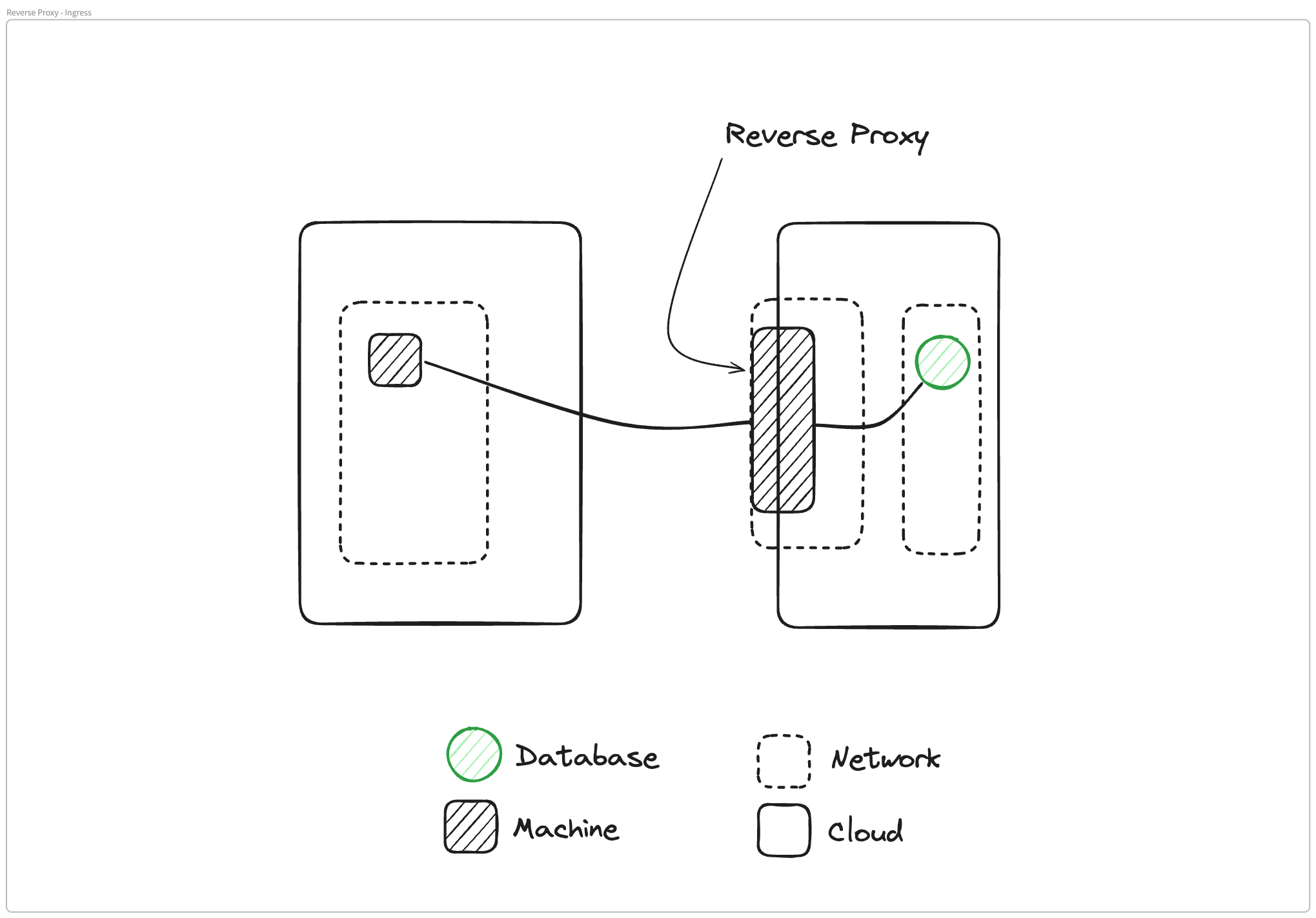

Matthew Gregory: When I think of reverse proxy, I essentially have this diagram in mind. I had an application that was running in my cloud environment, running in a private network, and I wanted to give access to the rest of the world.

Virtually what I have done is I have moved an application that was safe inside of my cloud, inside of my network, and I have virtually moved it to the edge of the cloud and made it available on the internet. That's my model of a reverse proxy, which is a great use case for Ockam.io or any website.

It's running in a safe environment inside Vercel, but they need to make it available so that everyone listening to the podcast can go to Ockam.io at any time that they want to access our website.

A reverse proxy in that case probably looks like a load balancer. That's a perfect use case for taking something in a secure, private environment and moving it to the edge of the internet so that everyone can access it.

This is my mental model for what's happening in a reverse proxy, our private machine can go out to the internet, traverse the internet, and find this service publicly available on the internet.

Mrinal Wadhwa: Which is great when you want everybody on the internet to get to it, but if the goal was to allow a specific set of clients to get to it then we're opening too big of a door.

Matthew Gregory: We're opening the biggest door, everyone. We're starting with infinity and trying to get down to something finite. It's not an easy problem to solve.

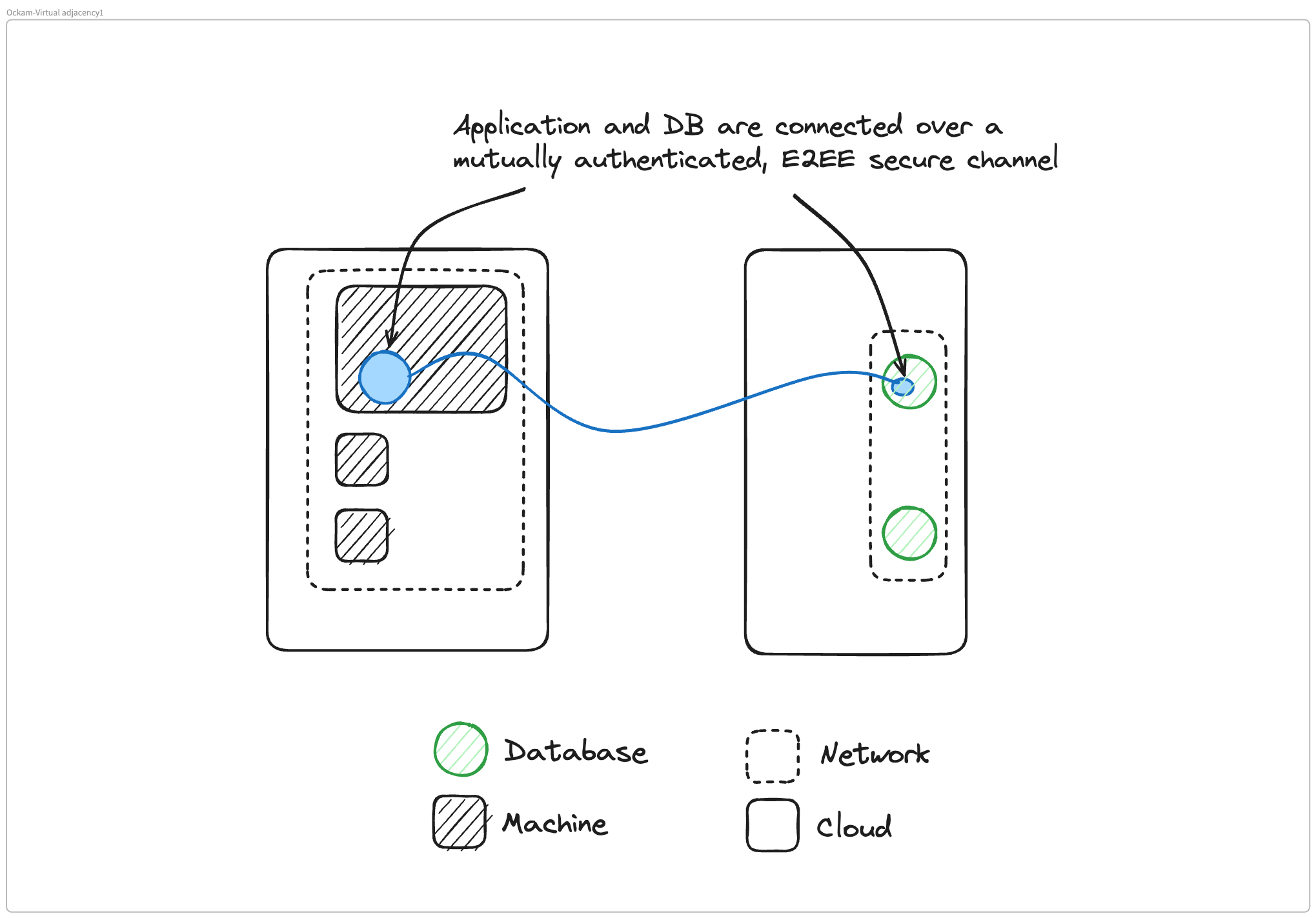

Let's move on to how this changes with Ockam. Mrinal, why don't you walk us through what we've done with Ockam and where this paradigm shift is? And what I'll introduce in this diagram is this new concept of the application inside the box.

When you start thinking about Ockam you have to think at the application layer. Why don't you describe what we've done here and how this diagram looks a lot different than the previous diagrams we've shown?

Ockam is a paradigm shift to the application layer - why Ockam is different to a network layer solution, like a VPN or Reverse Proxy.

Mrinal Wadhwa: With Ockam we think in terms of connecting applications. At Ockam's core is a set of protocols to do very similar things that we talked about in the case of a VPN. We have a routing layer that routes information across various machines at the application layer.

And then we have a secure channel implementation that allows us to set up end-to-end encrypted, mutually authenticated connections. The place where we're different from a VPN is that over that secure channel, we do not set up a virtual IP network. There is no virtual IP overlay network with Ockam.

Instead, there are two things you could do. You can pull the Ockam library into the application, and send a message to another application that is also using the Ockam library. And do that over an encrypted, mutually authenticated connection. In that scenario, these two applications become virtually connected and they're not connected to anything else. They only mutually authenticate each other and they only trust each other to send themselves messages.

But oftentimes, changing your application's code and pulling in a new library is a bigger project to take on. It may be sufficient to run Ockam next to your application and our building block for that we call Ockam portals.

In that scenario, what happens is we take your remote application, and we run a portal outlet next to it. So next to the database we run a portal outlet. Next to your database client, which is an application, we run an Ockam portal inlet. That portal is a single point-to-point virtual TCP connection over that secure end-to-end encrypted connection we established before.

Instead of creating a virtual IP network like a VPN, we create a virtual point-to-point TCP connection between two things that are running next to your application server and your application client. So your remote database server then starts appearing on localhost next to your database client application on the other side.

So your client code doesn't need to change. Your database code doesn't need to change. But effectively, what ends up happening is that the remote database appears on localhost next to the application that needs to access it.

And all the communication that's happening to that remote database is happening over this end-to-end encrypted, mutually authenticated secure channel.

Virtual adjacency - a new concept.

Matthew Gregory: We're living in this world of virtual concepts and we have this concept at Ockam called virtual adjacency. Effectively what we have done is we've taken a database that's running somewhere else and virtually moved it directly next to the application that needs to access that data, and we make it available on localhost to that application. So virtually we're kind of getting back to this monolithic approach and Glenn, maybe you can describe why that's a benefit.

Glenn Gillen: That was one of my realizations, especially as a reformed developer. It always surprises me how complicated it is when you want to get two things to talk that aren't in the same network. You've got an RDS Postgres instance running in one place, and then you've got a Lambda function or a container running somewhere else that you want to access that database.

I know what to do in that scenario. It's a dozen different things I need to configure in Terraform to set up security groups and all the other things to make that happen. It's a lot of work. We've evolved into this over time and there are good reasons for that.

I wouldn't trade the reliability, availability, and scale benefits you get from doing that. But the sacrifice is the simplicity of having everything in one box that you scaled vertically if you ever needed to, and everything lived on that.

Your database, your web server, it was all there. And then you'd eventually pull the database out to something else. It was still on the same network, but things were kind of easy. It was a simple mental model to get your head around.

You don't have to worry about the dozen things that you need to configure in Terraform to make it work. It's a smaller surface area for you to consider the risk implications as well. You protect the boundary of that one box and things are good.

There are two things I love about this virtual adjacency concept once I got a taste for what it was. One, it's a simple mental model as a development construct. You just access localhosts. The way I access that database and all the bits that have to happen for the database to be able to talk to my app have been abstracted away. From a vulnerability surface perspective as well, it's now simplified. I only have to worry about the ends of those two things. I don't have to worry about every single thing in between that I have to get right for it to be secure.

As long as I can make sure that only those two things can talk to each other, we're good. I've solved my security problem. It's bringing back the benefits you had from that simplicity without sacrificing all the other benefits we've gotten from the cloud over the past couple of decades.

How Ockam isolates data-in-motion to only two connected applications.

Matthew Gregory: Mrinal, tell us a little bit about the difference in how applications are isolated with Ockam versus that scenario we talked about with VPNs. Because with VPNs we talked about two machines in the same network, but now we're talking about an application running inside of a machine with a virtualized adjacency to a remote database. How do we have to think about security in that network, where we have this data that's now been moved over into this other machine? How should we be thinking about that?

Mrinal Wadhwa: To pull on something Glenn said earlier, there is no virtual cable connecting the machine that has the application to the machine that is running the database at the IP level. Those two machines are not on the same network. In this model, all that's possible is a single TCP connection to the database. That's it, right?

So because there is no connection at the IP level, not only are these two machines not on the same network but I can't laterally move from one virtual IP network into another one by doing scans and finding ways to jump around. Because there is no IP network for me to jump around in, there are no scanning tools I can run there.

What I can do is make a TCP connection to the database server, and only that database server. So the benefit from the point of view of the side that's running the database service here is that the application clients and anything else that might be local to the network where the application client is, can't enter this network at all.

From the point of view of the application client, what's nice is that it doesn't need to think in terms of remote names to remote IPs to resolve. It's all just localhost. So you have a localhost address at 127.0.0.1, and you have a port and you make connections to it as if the database was a single process running on that same machine. So it simplifies how connectivity happens there.

Behind the scenes, we are still making the connection happen. To do that we're doing all the things a VPN would be doing, which is we're routing the network, handing data over from one TCP connection to another TCP connection, we're doing NAT traversal in various ways. And very similar to the more modern VPNs that use WireGuard, we're also using a Noise Protocol framework-based secure channel that sets up this end-to-end encrypted channel. But all of that, you as the application developer don't have to worry about.

All of that just works. You run a command next to your database to start the portal outlet. You run another command next to your application client to start the portal inlet. You've got this end-to-end encrypted, mutually authenticated portal, and both sides are not exposed to each other's weaknesses and only this one TCP connection can pass through.

Matthew Gregory: I think we skim over this a lot where we talk about Ockam being simple, and there's not that much else to think about. And the reason we can say that is because we're starting with the doors closed. In a door's open environment, you may have connected things with the VPN or reverse proxy, but there's a whole world of problems and hurt coming your way.

You've created a whole work list of trying to figure out how to shut all the doors and then monitor to make sure the right doors are shut and which ones are open. But the simplicity comes from that Ockam is starting from a default doors closed point of view, and then opening up exactly and only what is needed to do the very specific job that that application needs to do. So it ends there.

Mrinal Wadhwa: A really interesting point is that there is no door. It's not a matter of opening the door or closing the door. There is no door from this app to this database, it just doesn't exist. There is no path that can be taken to traverse this. Whereas if you had an IP layer connection, you can traverse the network to figure out what's going on over here in that other network.

That's the advantage here, the door doesn't exist.

Matthew Gregory: This example becomes stark when you're talking about sharing data between two different companies. Say you're a SaaS product and you need access to data that exists at your customer. This is a perfect use case where you want to give explicit access to only the data that the SaaS application needs and absolutely nothing else inside that network or any other processes that might go on in that network.

Glenn Gillen: How we got here as an industry is because of the gradual evolution of the way we used to do things. I've talked about the virtual cable, we've taken things that were familiar to us and physical and then turned them into virtual things that we can do. This is how you end up in a place where you're connecting networks to solve these problems. There are absolutely still cases where that's exactly what you want to do, but there's also a whole bunch of cases where we're using that tool, but it's the wrong tool for the job.

We never wanted to connect the two networks between those things. What you wanted to do was connect applications. That's what we've been wanting to do for decades, but we haven't had the right tools and we've made the best with the tools we've had. That's the mindset shift here.

Let's give you better tools that map to what modern needs are, rather than forcing you to shoehorn the existing approach into what you're trying to achieve.

Day 2 debacles in distributed cloud architectures

Mrinal Wadhwa: That's a really good point. The example Matt was talking about was a SaaS application wanting to reach some data source inside a customer's environment. At no point does someone want their SaaS vendor in their VPC, that's never the intent. But effectively, that's what we end up creating.

If you look at how various integrations to SaaS vendors work, we end up giving them access to the VPC with specific roles inside the VPC and so forth. And then we get into this exercise of, how do we control their access inside the VPC. But we don't really want that. What we want to give them is access to a particular service in our VPC so that they can make very specific queries on that service.

Instead what they end up with usually is broad access into my network, which I have to control and protect in various ways. People do all sorts of things around this. We'll not expose it to the internet, we'll try to do some sort of private connectivity, or we'll expose it to the internet, but we'll set up some firewall rules that only allow very specific IPs to enter.

And then if those IPs change, you have to do those rules again. Or if the SaaS service is running in AWS, we'll have to IP allow a very vast range, right? All sorts of problems emerge from the fact that we end up connecting networks when we intend to just connect apps together.

Glenn Gillen: We've seen this multiple times where, for your operational overhead, you've tried to simplify your infrastructure by running a decent chunk of things in a single VPC. You have some data store and now the SaaS vendor wants access to that, but it's too big of a thing to access.

Wouldn't it be great if we had the workload they need to access in a separate VPC? So early on in your journey, you're forcing teams to have this perfect foresight into all the different permutations, or over-engineer isolation, just in case there's some future state where you might need to get someone access to something. And then you jump through all these hoops around transit, VPCs, and all this other machinery you put around your environment to close the doors to some extent and isolate stuff. Then it gets more complicated if you are on GCP and the SaaS vendor is on AWS, how do you connect there?

You can't use cloud-native tools. There's never a single solution, and if you're multi-cloud, it's a complicated mess with a dozen different ways to do it depending on which combination of things we need to solve for this particular vendor. It's too much to think about. You can't hold it in your head, and as soon as you can't hold it in your head, that in and of itself is a risk. Who understands the full picture?

Mrinal Wadhwa: Every time I've seen those types of topologies, usually if you talk to the people managing that infrastructure, they say they would like more segmentation, but it's too complex to segment given we have a bunch of stuff running. Usually that platform team or that IT team will say no to such a request.

And they're coming from the right place, because they're looking at the risk and going, if we let this happen, bad things could happen. But the person who needs that connectivity to get some business value either gives up and doesn't adopt the SaaS product, or they escalate and they go over that administrator's head and get the connection, but now effectively have caused the risk to enter the company. So you end up with not enough segmentation, and you're exposed to this attack or this vector from various sorts of hackers and things like that.

It gets complicated very quickly because you have to have a perfect plan when you don't know what the future state will be. Or you try to incrementally deal with it and end up with a lot of complexity in that topology.

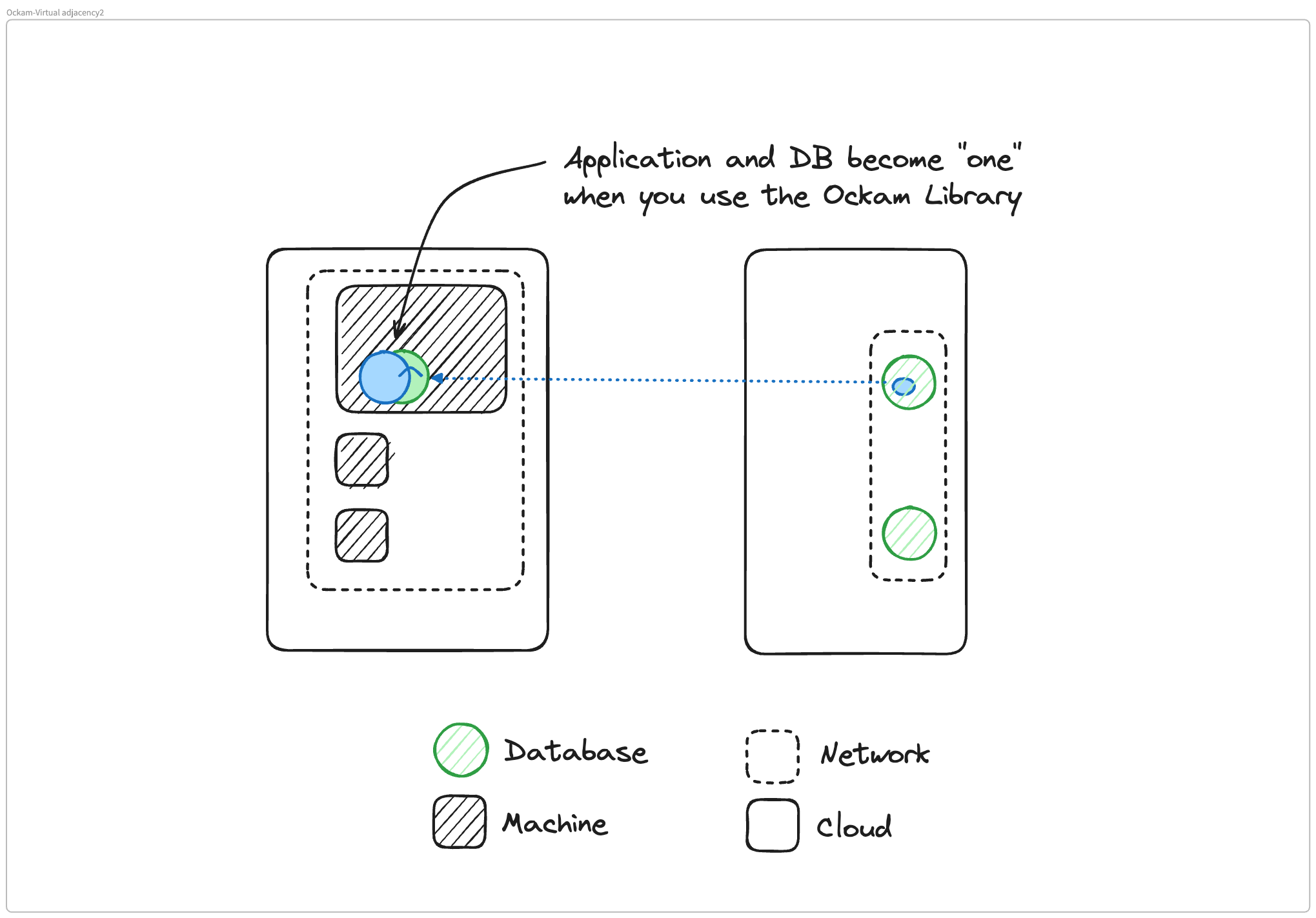

Distributed applications, DBs and processes become 'one' when you use the Ockam Library.

Matthew Gregory: Let's go back to where we started. We could listen to that solutions architect at Google Cloud and run our entire enterprise in one VPC and Google Cloud, right? Kidding aside, I saved one thing for last because this is a little bit of a mind-bender. When we describe this concept of virtual adjacency, we have our remote database running virtually like its own localhost right next to our application because of Ockam command. There's another way to consume Ockam and this is even more in the direction of a monolith. We can use the Ockam library, which we use to build Ockam command. And in this scenario, that database looks like a function call inside our application.

So we're getting into this monolith model in this abstraction because we're using the library and we're building Ockam directly into our application. This is another cool way of using Ockam for anyone who wants to use the library instead of Ockam command. This escalates the level of security and the perimeter down to the application itself. The architecture here is pretty neat.

Mrinal Wadhwa: There are tradeoffs between the two approaches.

If you use Ockam as a library and integrate it into your application, it's a little bit more work. It's not very complex. You'll notice our library examples are 20-30 lines of code. It's not complex to do this. In those 20-30 lines you get these end-to-end encrypted, mutually authenticated connections with attribute-based access control on top.

It's fairly straightforward but does require you to change your application code. But if you do it, then the two applications that you want to communicate will become virtually connected only to each other.

The remote database in our earlier examples doesn't become exposed on localhost to everything else on the machine. It is only available to the client application. And that's a nice benefit that you get if you're willing to make the trade-off of actually changing your code.

If you're not willing to make that trade-off, or you have a set of protocols that the application client and server already speak that you don't want to change, then, in that case, you can use Ockam command with Ockam portals. That way, you don't have to change anything. We just take your TCP connection, we carry it over the Ockam end-to-end secure channel. So both of these approaches have their own set of tradeoffs.

Glenn Gillen: Application can mean a lot of things to different people, some people will refer to an entire microservice cluster as an application.

But my mental model for this is process to process secure connectivity. When we go back to my example of using a VPN to connect to a Postgres database, that's not what I ever wanted. I wanted the Postgres PSQL command on my local machine to be able to connect to the Postgres process on some other machine.

That's all I needed to do, but I use VPNs to do it. So it's not application in some big sense, it's a fine-grain level of connectivity that gets established with Ockam.

Mrinal Wadhwa: If you're using the Ockam library, that specific application process is talking to a remote application process somewhere else. As long as both of these speak the Ockam protocol by using the Ockam library, they can mutually authenticate only with each other, and then there are no other environmental components that are exposed.

It doesn't matter which machine they're running on, there is no way to get out of the application process. That's the granular application process to application process connectivity.

In the case of a VPN, you're creating this virtual IP network and your remote application is somewhere in that IP network that may be spread across hundreds or thousands of machines. Whereas in the case of a reverse proxy, you're taking a remote thing, putting it on the internet, and your client is just reaching out to something on the internet.

In the case of an Ockam TCP portal created using Ockam command, we're taking a remote thing and making it available on localhost next to your application client process.

If you use the Ockam programming library, we're taking a remote thing and putting it inside your application process, and you just call a function to access that remote thing. That's the levels of difference that end up getting created in different approaches here.

VPNs, Reverse Proxies, and Ockam are radically different solutions.

Matthew Gregory: Let me wrap up with that point.

When we think about what we get when we're using a VPN, a reverse proxy, or Ockam, we're getting different architectural diagrams. When you look at the glossy brochures of VPNs, reverse proxies, and Ockam, they start to sound pretty similar, but when you look at what you get, they're radically different.

And let's review. With the VPN, you're connecting a bunch of machines to a bunch of other machines and putting them all on the same network. That is the goal of a VPN, to have one network with all the machines in it. When we use a reverse proxy, we are taking a local service and making it available to everyone on the internet. If you want to run a webpage and have everyone on the internet access it, you want to run it on your local laptop and keep your laptop on so it's available all the time. Reverse proxy is a great way to do that.

And then with Ockam, what we're doing is taking applications that are running remotely and making them virtually look like they're all adjacent to each other, very similar to a monolith.

When you break them down and look at them from the virtual mental model, they're quite different from each other and they have different purposes, all of which are valid. It depends on what you want to do with each of them.

With that, we'll wrap up the second edition of the podcast. If you have any questions, let us know in the comments below. And if you have any suggestions for future episodes, send those our way also and we'll address them. We're doing one of these a week, so we have a lot to cover with that. Thank you for joining.

Previous Article

Episode 3: How a SaaS Product Manager should think about connections to customer data

Next Article

Episode 1 - The Founding Story of Ockam